1. Russian-Sweedish Skating Controversy

2. Nikolai Panin’s Name

3. The Calendar Myth

Russia and the Silence of British Newspapers

Russia won three medals in 1908, but did not make a splash with the international community. Unlike the Soviet age, in which western media paid great attention to ideologically fueled rivalry between East and West, Imperial Russia attracted no attention.

Source1

By analyzing British newspapers for mentions of Russia during the games, it becomes clear that the stereotype of a Russian backwater still held significant weight in the British imagination. Additionally, the silences – what the British papers avoided talking about or sidelined – revealed the unimportance of Russian medals.

Above Source2

1. British Papers Miss the Russian-Sweedish Controversy

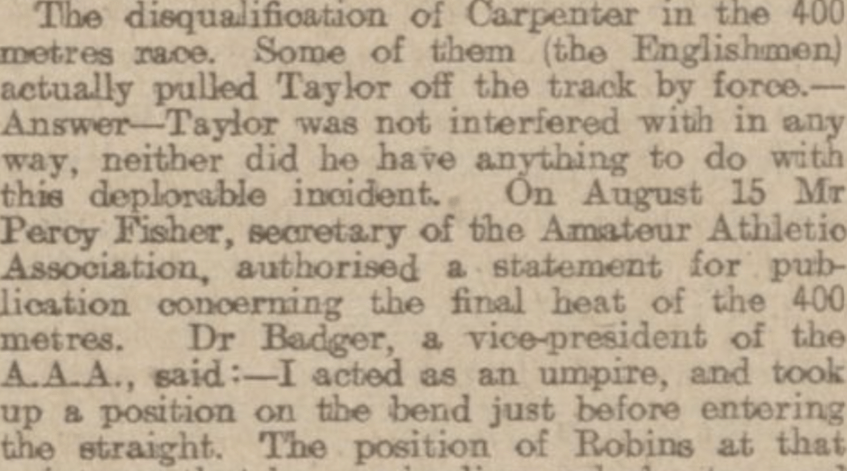

Beyond the mere scarcity of articles relating to Russian athletes, British newspapers actively chose to cover the British-American judging controversy over the equally problematic treatment of Nikolai Panin by his opponent Ulrich Salchow.

Britain vs. America

Both contemporaries and historians place emphasis on an American-British controversy in which Americans accused British referees of favoritism, especially in the light of the disqualification of an American athlete in the 400m dash.4

Russia vs. Sweden

At the same time, Russia was embroiled in a controversy that was almost entirely overlooked despite it having impacts on multiple medal results.

Nikolai Panin was originally supposed to compete in both special figures and free skating events against the Swedish world champion Ulrich Salchow.

But during the first free skating event Salchow yelled insults at Panin throughout his routine, forcing him to retire in protest. Despite Russian complaints, the event was swept under the rug by the Olympic Committee.5

Nikolai Panin was also omitted from Ulrich Salchow’s 1913 article on the best of modern ice skating and was even overlooked as late as the 1972 history of Olympic champions, further denying him international notoriety. Russian athletes thus suffered from silences imposed on them by the media.6

2. Nikolai Panin’s Naming Problem

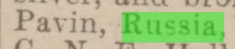

Despite winning a gold medal, British newspapers consistently made little effort to translate the Russian’s name, spelling his name wrong in a multitude of ways that often barely resembled the original.

Some mistakes were simple, like N. Pannin (two n’s) or falsely anglicizing his name to Nicholas. Some however were more notable like those shown below.7

3. The Calendar Myth – Was Russia Really Late?

One final piece to Russia’s entrance in 1908 was the continued belief by Western nations that Russia was a backward nation. Russia failed to attend in 1896 because of logistical challenges in getting their athletes outside of the country and did not have a defined system until 1912.

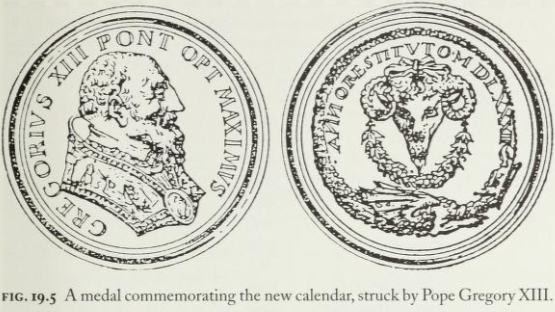

This manifested itself in a myth which claimed Russia arived late in 1908 because they were using

The myth that Russia showed up late because of their calendar is inconclusive. Popular magazine articles cite Biomechanics professor E.G. Richards in the claim but Richards fails to cite any sources of his own. It is true that the shooting team was disqualified for being 12 days late, but historical evidence is both scarce and tenuous.8

Regardless of truth, the fact that the myth existed at all was proof that the rise of Russian sport did not significantly impact perceptions of Russia in the west, even coupling them with backwardness despite victories over British and American athletes.

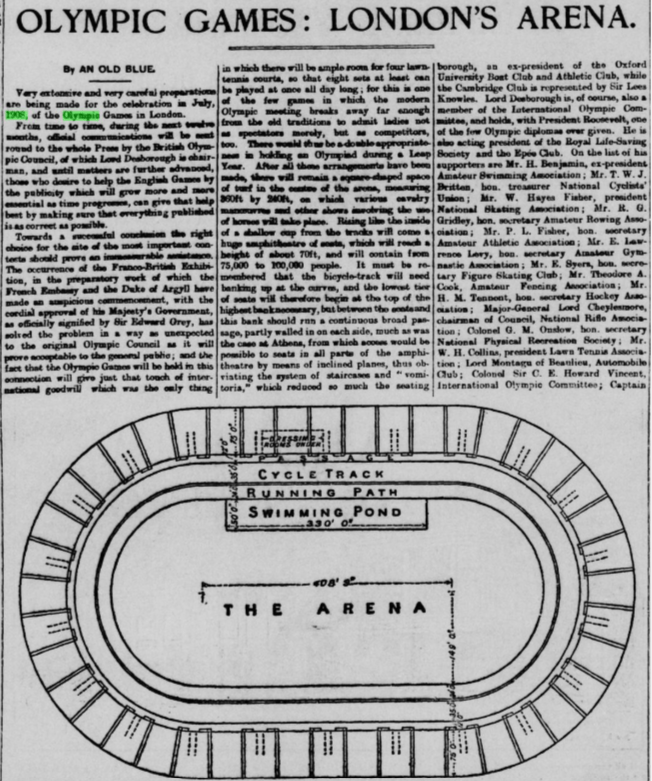

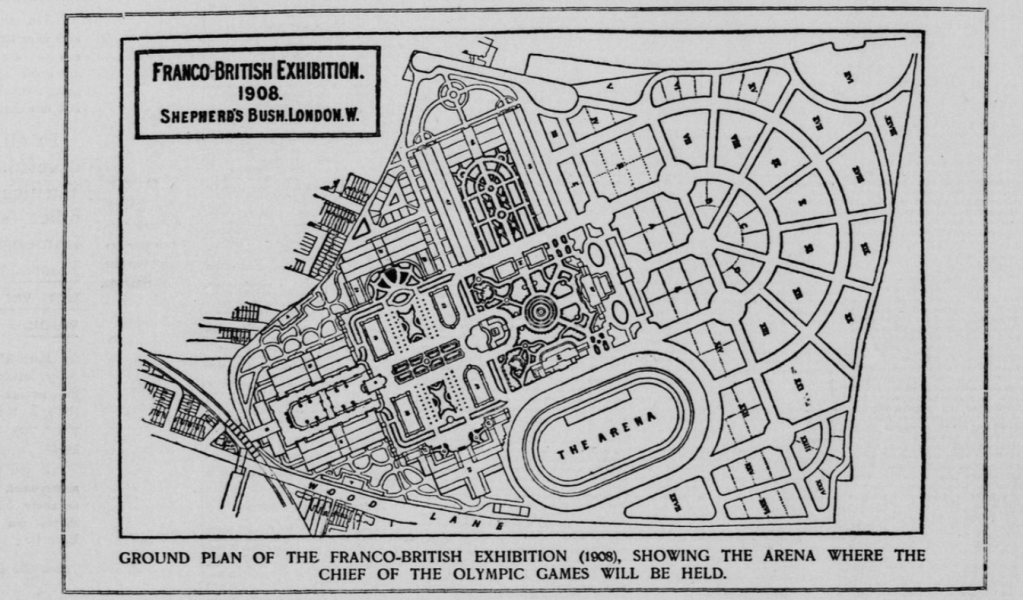

- “Olympic Games: London’s Arena,” The Daily Telegraph, April 1, 1907, The Telegraph Historical Archive. ↩︎

- “Olympic Games: The New Buildings Begun,” The Daily Telegraph, April 2, 1907, The Telegraph Historical Archive. ↩︎

- Aberdeen Journal. “The Olympic Games.” November 17, 1908. British Library Newspapers. ↩︎

- Matthew McIntire, “National Status, the 1908 Olympic Games and the English Press,” Media History 15, no. 3 (2009): 271–86. ↩︎

- Volker Kluge, “Nikolai Kolomenkin Did Not Consider ‘Panin’ to Be so Great,” Journal of

Olympic History, no. 1 (2014): 22. Alexander Smith, “Russia in the Olympic Movement around 1900.” Journal of Olympic History 10, no. 3 (2002): 46-60. ↩︎ - John D. Windhausen, “Russia’s First Olympic Victor,” Journal of Sport History 3, no. 1 (1976): 35–44. ↩︎

- For example articles see Daily Mail, “The World’s Best Skaters.” October 23, 1908, Gale Daily Mail Historical Archive. Dundee Courier, “Olympic Ice-Skating Championship,” October 30, 1908. British Library Newspapers. Evening Telegraph. “Olympic Skating Contest.” October 29, 1908. British Library Newspapers Archive. For an American example see The New York Herald (European Edition), “Fine Displays Given at Olympic Skating Tests. October 30, 1908. International Herald Tribune Historical Archive, 1887-2013. ↩︎

- “The Extra Mustard Trivia Hour: When a Calendar Defeated Russia in the 1908 Olympics.” December 30, 2013. https://www.si.com/extra-mustard/2013/12/30/the-extra-mustard-trivia-hour-when-a-calendar-defeated-russia-in-the-1908-olympics. For the original claim as well as images, see Edward G. Richards, Mapping Time: The Calendar and Its History (Oxford University Press, 1999), 245-250. ↩︎